by Julia Seibert

When it comes to satellites, bigger is not always better. As last century’s satellites lurking out in orbit look on, their successors are evolving so rapidly to the point where they are almost unrecognizably different. The new kids on the block are spiffier, cheaper, and – notably – much smaller.

The precise parameters of small satellites – or SmallSats, in industry jargon – vary depending on whom you ask, with definitions ranging from up to 180kg to 1,200kg (500kg is a common benchmark for many analysts). What is agreed upon, though, is that their presence has utterly revolutionized the modern space industry. This upheaval, according to Justin Cadman, co-CEO of space analytics firm Quilty Space, started about a decade ago, brought about by a trifecta of lowered launch costs, miniaturization and standardization of technology, and an industry more accepting of risk. Is the age of the SmallSat here to stay?

Top Small Satellite Companies

1. Spire Global

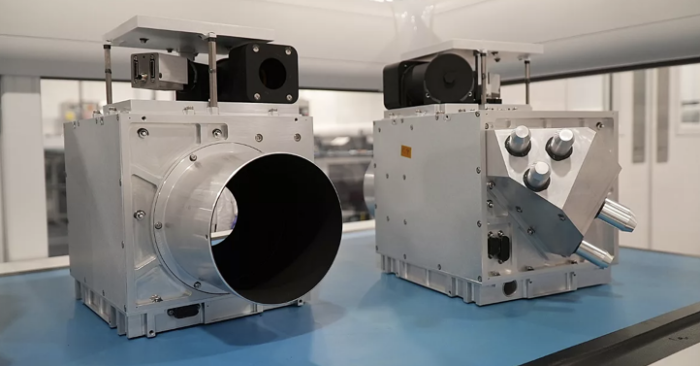

Founded in San Francisco in 2012, Spire found its feet while the SmallSat revolution was still in diapers. Today, however, the company has multiple offices around the world and boasts at least 112 orbital SmallSats, which beam down dizzying amounts of data. These sats, called LEMUR, are CubeSats: SmallSats consisting of one or several standardized satellite units, which are manufactured using commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components, making them relatively cost-efficient. Spire uses them for collecting Earth information (including subterranean, atmospheric, and weather data), as well as the monitoring of maritime and aviation patterns.

As noted by Wired, Spire’s talent lies not in snapping pictures of the Earth. Instead, the LEMURs collect signals from GPS satellites from the other side of the Earth, using the beam’s refraction through the atmosphere to calculate weather data. The satellites also track broadcasts from ships and planes. This way, Spire can provide its customers with information on everything from hurricanes to pirates. Spire also offers accommodation for customer payloads aboard its satellite platforms, which it claims can go from design to launch in six months.

2. Planet Labs

Speaking of Earth observation, monitoring the planet visually from orbit constitutes a major market niche in the space industry. San Francisco-based Planet Labs, founded in 2010, is the poster boy for commercial efforts to do so. The company has about 200 satellites in orbit, most of which are what the company calls Doves. These CubeSat-based machines are a little smaller than a microwave, and – as noted by cofounder Will Marshall – can take pictures ten times the resolution of traditional imaging satellites while being a thousand times lighter.

The company also operates a slightly larger fleet of satellites (still CubeSat-based) known as SkySats, which can revisit a given sight several times a day and capture it in 50cm resolution. In addition, Planet provides an analytics tool ‘powered by deep learning and computer vision’, which automatically tracks changes in an area of interest. Planet’s customers, it claims on its website, are based in agriculture, government, and commercial mapping. In recent times, the company often makes the news with its imagery of the war in Ukraine, in which commercial satellite companies like Planet play a substantial part.

Visit company’s profile page.

3. GHGSat

Imaging data from commercial satellites can also be useful for monitoring pollution and climate change – so much so that GHGSat built its business around this particular mission. The Montreal-based company currently has nine satellites in orbit, weighing in at about 16kg each. These SmallSat are tasked with a simple mission: track greenhouse gas emissions from orbit and follow them to the source. Another seven sats, ordered from Spire, are set to launch in the next year or so to increase frequency and coverage. GHGSat’s first satellite, launched in 2016, monitored both CO2 and methane emissions, but the company soon focused only on methane.

Today, the company can pinpoint methane emissions to single facilities, making it easier to hold emitters accountable. Among others, GHGSat has partnered with oil and gas giant ExxonMobil to help it track methane emissions from its sites in Texas and New Mexico. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg; while methane is more potent, carbon dioxide is emitted much more frequently and is by far the most abundant polluting gas. Therefore, GHGSat is beginning to refocus its attention on carbon dioxide, announcing its first CO2-specialized satellite in early 2023.

Visit company’s profile page.

4. Starlink

Starlink, operated by American launch giant SpaceX, constitutes another growing vein of the satellite industry: internet. Starlink satellites account for roughly half of all active satellites currently in orbit, and while newer versions of these machines surpass some definitions of SmallSats, the company is nevertheless a SmallSat giant with thousands of them in Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

This low orbital altitude is a linchpin in the company’s business model. Satellites closer to Earth provide a faster connection, but this also means that each satellite has only a limited ‘view’ of the planet, and cannot hover over one zone indefinitely like those further out in geostationary orbit (GEO). The solution is to build a constellation of at least 12,000 of them in order to cover the entire globe.

Satellite internet can be especially useful aboard planes and ships, as well as for those living in isolated areas. It has also shaped much of the war in Ukraine, with Starlink often providing the sole means of connectivity for both civilians and the military. After a saga of disagreements from SpaceX regarding the satellites’ use in the war and the source of the donation, the company is now under contract with the US Department of Defense to provide services in the area.

Since its first satellites launched in 2019, Starlink is only beginning to make money and is falling somewhat short of its ambitious goal of having 20 million subscribers in 2022 (it had just 1 million). With new satellites launching every few days, SpaceX is set to double this customer base in 2023, which, according to space analysis firm Euroconsult, would have Starlink account for 40% of SpaceX’s 2023 revenue. This would not be by accident; SpaceX hopes to use cash from Starlink to fund its loftier goals, such as developing its mega-rocket Starship and building a city on Mars.

Visit company’s profile page.

5. Space Forge

Though Wales-based Space Forge currently has no satellites in orbit, it represents SmallSats’ ability to enable the emergence of entirely new industries – in this case, in-space manufacturing. The company hopes to use satellites as mini orbital factories that harness the usually hostile characteristics of space – lifeless, vacuum, lack of gravity – to improve the quality of products such as semiconductors and pharmaceuticals. According to the company founder and CEO Josh Western, in-space manufacturing can yield semiconductors up to 100 times more efficient than their terrestrial variants.

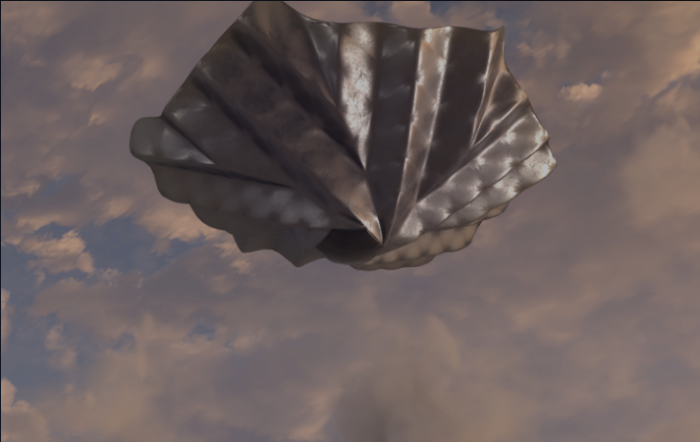

It starts with SmallSats. Materials would launch aboard the company’s microwave-sized satellite, called ForgeStar, and stay in orbit for up to six months while the products are manufactured. After returning to Earth with the products, the satellite should be fully reusable. However, this is still highly theoretical since the satellite is still in its early demonstrative stages (ForgeStar-1A, which would be the company’s first orbital satellite, will launch in 2023 or early 2024; its predecessor tumbled into the sea aboard the ill-fated Virgin Orbit launch in January 2023). Still, as reported by AviationWeek, the first generation of the ForgeStar should already be capable of producing 100 chips a flight. The larger second-generation ForgeStar-2, planned for 2025, would produce a whopping 100,000.

Visit company’s profile page.

How Small Satellite Companies Impact the Space Industry

By making it easier for industry to reach orbit, SmallSat companies have made it clear that there are palpable commercial opportunities beyond the atmosphere. Some of these were already obvious before the widespread commercialization of today; Earth observation, for example, has been an ongoing governmental objective since the dawn of the first space age. However, the emergence of SmallSat companies completely changed how this is done. The availability of SmallSats helped more commercial companies join the fun, and not only presented governments with a cheaper way of obtaining such data but also allowed private customers to access it.

Now, the Earth observation sector is a full-blown commercial field, rather than a secretive governmental endeavor. The same could be said for other sectors, such as communications and military applications. Through the use of small satellites, for instance, Starlink turned the satellite communications field on its head, also influencing plans for China’s 13,000-strong internet constellation GuoWang. On the military side, the US Space Development Agency (SDA) is contracting commercial companies to build a SmallSat constellation for missile tracking and communications.

In addition to turning existing sectors into industries and expanding their scope, SmallSat companies are contributing to the emergence of new industries altogether. As described by Northern Sky Research, a space market research company, they have ‘bridged the gap between innovation and implementation’. Thanks to a lowered access barrier to orbit through SmallSats, it is now possible for companies with an appetite for risk to send up missions without breaking the bank. Space Forge and its peers (such as Varda) are one example, as is AstroForge, a company that is starting with SmallSats on its mission to mine asteroids.

The rise of the SmallSat has also led to the preeminence of satellite constellations, which are being developed by an ever-increasing number of companies. The reason is simple: though individual SmallSats might not be as powerful as bigger ones, their strength lies in numbers. A legion of SmallSats zooming around Earth in LEO can provide quick, accurate coverage without the need for gigantic antennae to catch faint radio signals out in GEO.

Compared to single large satellites, SmallSat constellations are also more resilient, as an outage of one SmallSat does not leave the rest of the constellation in limbo. Due to their location in LEO, SmallSats deorbit within a few years of their launch, meaning constant launches are needed to replenish the constellation. This can be logistically irritating for companies, but it also allows updates and changes to be made to newer-generation satellites. Though this trend of constellations was largely brought about by SmallSats, it is now extending to larger satellites such as Starlink’s latest models, Amazon’s Project Kuiper, and several other companies.

The influence of SmallSats has also seeped into the launch industry. The satellites’ popularity has led SpaceX to offer rideshare missions specifically for SmallSat launches, known as Transporter missions; these have proven extremely popular, with 682 spacecraft delivered to orbit so far. SpaceX also recently announced Bandwagon, a similar project that would shuttle satellites into a mid-inclination orbit. SpaceX aside, several young launch companies in China, India, Europe, and the US are building their vision specifically around the SmallSat launch. Many offer bespoke launches to send satellites into highly specific orbits, whereas rideshares like SpaceX dump them all out in one go. Some of these companies, including the UK’s Skyrora and Germany’s Rocket Factory Augsburg, are also developing Orbital Transfer Vehicles (OTVs) that can tug satellites to specific orbits. However, many of these young launchers are just taking their baby steps, and their market share is already threatened by SpaceX’s dominance and bargain prices.

Challenges Faced by Small Satellite Companies

Despite the promise shown by SmallSats, several challenges persist. The most obvious is that SmallSats’ size and mass constraints limit their means of propulsion as well as any extra gadgets. As noted by Alexandre Najjar, a senior consultant for Euroconsult, the evolution of Starlink resulted in its graduation from the SmallSat class as it began to include new features such as laser links. Even within the realm of SmallSats, average sizes are going up to maximize performance. ‘It’s like mobile phones,’ says Renato Panesi, chief commercial officer of Italian rideshare operator D-Orbit (as reported by SpaceNews). ‘They were big in the ’90s, and then they became smaller, only to become bigger but more powerful’.

In another report by SpaceNews, Euroconsult principal adviser Maxime Puteaux explains that while SmallSats are cheaper, decreasing launch costs means that companies will shift to larger satellites for newer generations of their products. Since this trend is still in its infancy, Euroconsult estimates that SmallSat launches have yet to peak, but will begin to drop at the end of the decade. This trend is likely to be further influenced by the availability of new heavy launchers such as SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn, which would make launching bigger satellites more affordable. Still, Euroconsult foresees a ‘steady and healthy’ growth of the SmallSat market over the next decade.

Another issue highlighted by Euroconsult is inflation, which the firm states could limit the scope of some SmallSat constellations. Supply chain issues and increased costs of raw materials such as metals as well as limited supply of semiconductors are all contributing factors. This is not desirable in any industry but spells especially bad news in space, where it can take years to turn a profit (a challenge in itself). Even Starlink, with its deep pockets and relentless launching, is just beginning to rake in some cash. For younger companies with fewer funds eyeing unproven industries, investors could be turned off by decades-long timelines for a goal whose attainability is already questionable (space mining startups Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources both fell to these issues). This qualm, coupled with inflation, is a general one for the space industry but is already affecting the SmallSat market. As reported by SpaceNews, D-Orbit has noticed a slowing growth of satellite constellations, to which inflation is a contributing factor, so Euroconsult.

Another less apparent challenge presented by SmallSats is managing space debris. While many SmallSats are designed to deorbit within a few years, the sheer amount of them – Euroconsult predicts 26,104 to launch by 2032 – presents a growing concern for any orbital activity. SmallSats are not alone in contributing to the issue, but they come with two unique problems: their small size and limited means of propulsion.

A 2019 NSR report estimated that about 39% of SmallSats launched within the decade will be under 10cm: the threshold beneath which monitoring orbital objects becomes more difficult. Adjacently, some SmallSats’ limited maneuvering capabilities mean that dodging oncoming objects could be tricky. With few plans to mitigate this problem apart from a 5-year deorbiting rule slapped on by the US’s Federal Communications Commission (FCC), any orbital plans – be it in-space manufacturing, tourism, refueling, or even other satellite activity – could be threatened by the oncoming tsunami of SmallSats.

Future Trends

Despite its challenges, Euroconsult predicts the SmallSat market to reach a value of US $110.5 billion over the next decade; manufacturing is to make up 76.3%, launch 34.2%. The clear winners of this boom will be commercial players, who the firm predicts will account for 82% of mass launched to orbit during this time. Constellations will continue to reign supreme, with 85% of the 26,104 SmallSats predicted to launch by 2032 being part of one. The ongoing increase of SmallSats’ masses also shows no sign of stopping.

Outside the commercial industry, governmental contracts are likely to continue to provide some shelter in the storms of inflation and questionable profitability as the geopolitical importance of space grows (as demonstrated by the conflict in Ukraine). Euroconsult states that especially in the US, defense entities will continue to sponsor commercial SmallSat deployment, such as the SDA’s constellation. Governments are also important customers for Earth observation companies like Planet Labs, and this relationship is unlikely to change.

As seen in the list above, most leading SmallSat companies hail from the US, where the commercial space industry is at its most developed. However, according to Euroconsult, Asia – led by China – is set to increase its number of SmallSats by ten within a decade. Two of China’s state-owned enterprises – China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) – are reportedly capable of producing over 200 yearly SmallSats each. CAST, as well as the Innovation Academy for Microsatellites (IAMCAS), also state-owned, are the main contractors for the GuoWang constellation, as reported by SpaceNews. In addition, a 12,000-satellite broadband internet service, G60 Starlink, is in the works by the Shanghai government.

Aside from its state-owned enterprises, China’s commercial SmallSat companies are less developed than the US’s, but they exist; Galaxy Space, Spacety, Commsat, and ZeroG Lab are some examples. China is also home to a gaggle of launch startups, which could allow commercial projects to come to fruition and help capture international markets.

As both China and the US begin to eye up colonization of the moon and beyond, SmallSats could follow them there. SmallSats are being used by NASA to study the moon, with missions such as IceCube and Lunar Flashlight having scoped out water ice and possible landing spots for the upcoming Artemis crewed landings. For deep space missions, NASA proposes sending constellations of Cubesats to faraway worlds as a cheaper way of monitoring them; only one bigger satellite, or ‘hub’, is needed to relay information back to Earth and perform more complicated tasks. By extension, this system could also be used to establish communications from humans on such a world back to Earth, and this is being envisioned by several players. China, for one, is planning a lunar satellite constellation to aid its crewed missions and has a relay satellite in place (though these are not necessarily SmallSats). In its Terms of Service, Starlink also mentions providing coverage of the moon and even Mars.

Many things about SmallSats are nebulous – their viability, size, and sustainability in orbit, to name a few – but their impact on the industry is undeniable. As a vital stepping stone for many hoping to do business in orbit and beyond, their simplicity and versatility have brought space closer than ever before, bringing with it opportunities and risks alike. The pressing question now, though, is what comes next. As the industry’s attention drifts towards deep space following major national moon missions in the next decade, will SmallSats carve out a niche of their own?

For more market insights, check out our latest space industry news.

Featured image: 3U satellite. Credit: Spire Global

Share this article: