It was the highest honor a space company could hope to attain: landing humans on the moon for the first time in over 50 years. NASA’s commercial Human Landing System (HLS) program opened up the most climactic part of its lunar Artemis missions to commercial companies, who competed fiercely for the coveted contracts. Among them was Dynetics, a subsidiary of defense giant Leidos with little to no experience in human space. Twice, the company found itself in the final selection round – and twice, with the prize just within reach, it was snatched away.

SpaceX and Blue Origin snapped up the contracts in 2021 and 2023, respectively, while Dynetics’s HLS design was deemed suboptimal. Still, NASA is keeping its options open regarding missions after 2030; when the time comes, might Dynetics finally stand victorious?

Table of Contents

ToggleOverview of Dynetics HLS

First, a little disclaimer: it is slightly tricky to discern what Dynetics’s HLS actually is since the company’s submission to NASA mentioned two different landers: the Autonomous Logistics Platform for All-Moon Cargo Access (ALPACA) and the Crewed Demonstration Mission (CDM) vehicle. The exact differences have not been made public, and the company’s updates and renders mostly refer to just one design.

It appears that even Dynetics had trouble keeping the landers apart. In the May 2023 Source Selection statement following Dynetics’s second loss, Jim Free, Associate Administrator for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate of NASA, mentioned that it was unclear which system was flying what mission. The CDM vehicle, it seems, met fewer requirements than ALPACA. However, the document evaluates the company’s approach and capability as a whole instead of untangling the differences between the landers, which this article will strive to do as well.

Dynetics caught the attention of NASA early on, becoming one of 11 companies to win funding for preliminary studies of lunar landers in 2019. In 2020, Dynetics’s design – then slightly different from today’s – was awarded a US $253 million contract for further development. Competitors SpaceX and Blue Origin were also selected. A year later, NASA was to choose the companies that would return mankind to the moon as part of the Artemis III mission, scheduled for 2025.

In an upset, the agency picked only SpaceX, prompting Blue Origin and Dynetics to complain to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). The decision was upheld, and – after Blue Origin sued NASA and lost – the case was closed.

Or so it seemed. Later that year, NASA handed out smaller contracts to Dynetics and four other companies for lander design maturation. Then, US Congress commanded NASA to select another lander from anyone but SpaceX to boost competition. The result was the Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) contract, for which bids closed in December 2022. This new contract was for the Artemis V landing in 2029; NASA had already contracted SpaceX for Artemis IV. Blue Origin and Dynetics saw their chance and revamped their designs for another shot at the win, but this time it was Blue that walked away with the prize in May 2023.

Dynetics’s HLS is centered around business and a lunar economy, which is reflected in its design. As mentioned by Free, the company’s plan ‘describes a strategy for commercialization that enables the firm to pursue additional customers, markets, and missions for its lander architecture and helps to enable the development of a commercial cis-lunar economy’. By using NASA as its first customer and proving the apparent viability of its design, it would help kickstart such an economy, which it would dearly need to justify its lander. Dynetics asked NASA for US $9.08 billion to fund the 2021 version of its design (compared to the roughly US $3 billion bid from SpaceX). Its 2023 proposal’s cost was also described by Free as ‘substantially higher’ than Blue Origin’s, who ended up getting US $3.4 billion.

See also: Human Landing System (HLS)- Everything you need to know

Dynetics HLS Design and Features

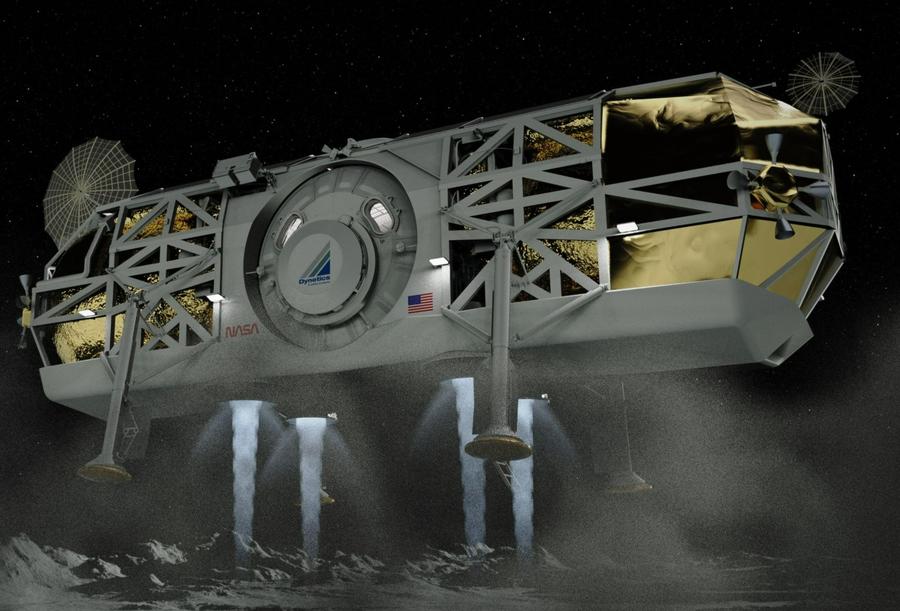

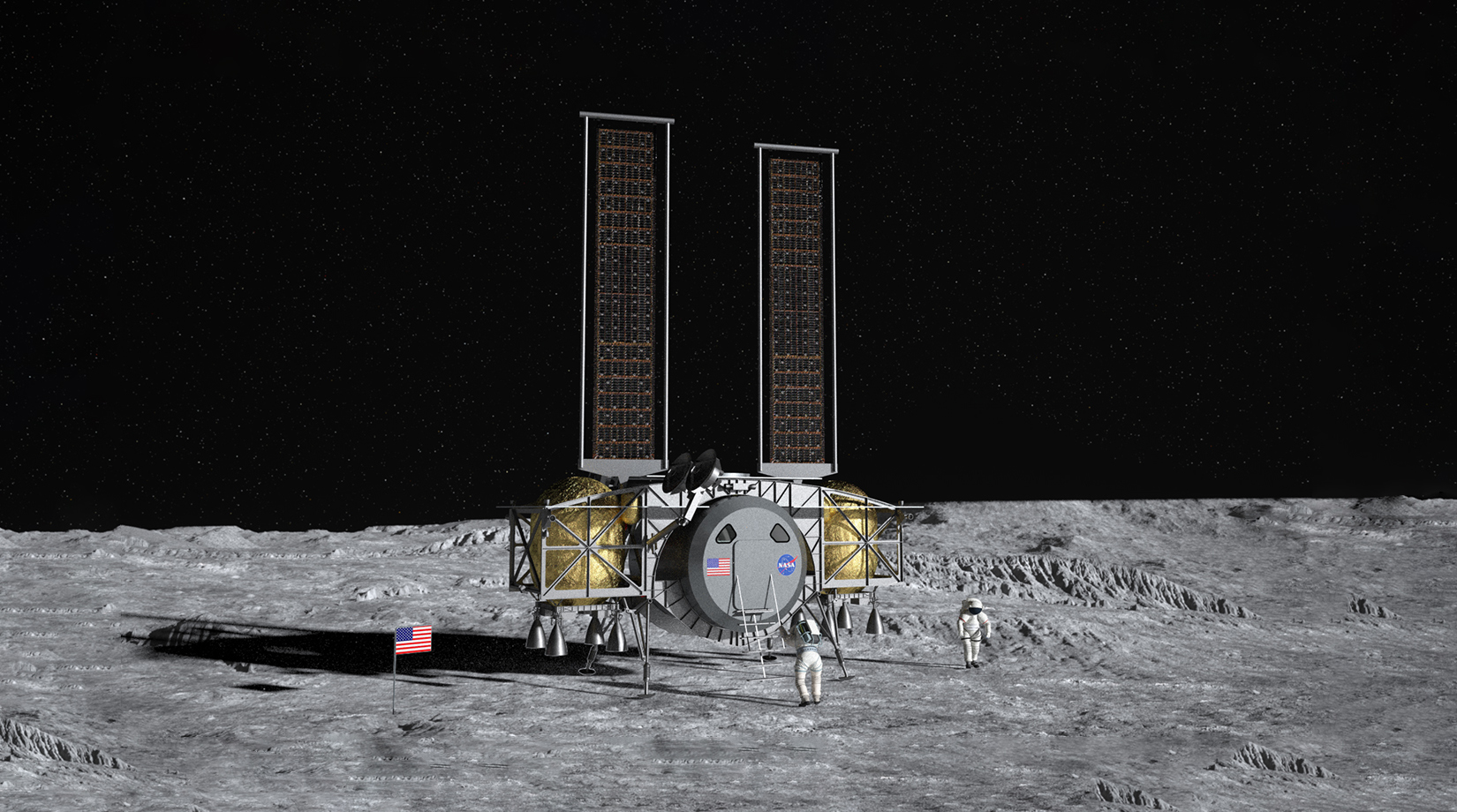

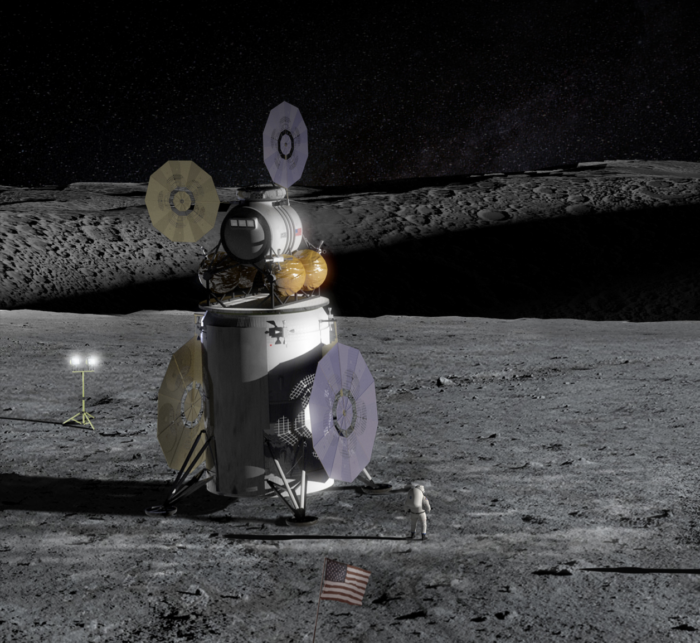

The design itself is quite unique, featuring few similarities to SpaceX or Blue Origin’s HLS proposals. Vaguely reminiscent of a potato, the lander is of a ‘low-slung’ design: wide while not particularly tall. This creates a lower center of gravity which, the company claims, can help it land in a diverse variety of sites.

The crew module sits in the middle of the lander, with the lunar surface just a few steps down from the door. As of 2020, the vehicle should be capable of carrying four astronauts to the lunar surface but can only serve as a habitat for two. In his Selection Statement, Free noted that it is unclear whether the updated design meets the requirements for four astronauts.

As for non-human missions, a cargo variant of the lander (ALPACA in this case) appears to be planned, capable of bringing 30 metric tons to the lunar surface if the payload is integrated with the vehicle and does not return to orbit. This shrinks to about 12 tons if the cargo is to be offloaded and the lander reused.

The propellant tanks, carrying liquid methane and oxygen, are located on either side of the crew module. Previously, these had been of modular design, with each tank consisting of a spaceship that would launch separately and rendezvous with the lander in space. This method seems to have been ditched in favor of permanent tanks to be fueled once launched. The most recent iterations of the design show four engines on the bottom of a lander (previous visualizations showed eight). For onboard power, the lander features two long solar panels extending upwards from the roof. To protect these and other sensitive surfaces from the harsh lunar dust, Dynetics is developing a so-called Electrodynamic Dust Shield (EDS), wherein minuscule wires built into these surfaces provide protection against the stuff.

Again, the whole design appears to have been built around the promise of business. The most obvious factor is reusability: ‘It needs to be reusable and affordable, so our intent is that [the HLS] will be reusable, basically from the start’ said Andy Crocker, HLS program manager at Dynetics, in 2020 (as reported by CNBC). ‘We want to be able to reuse our spacecraft to be able to carry many different payloads to the surface… it can be part of a broader lunar economy, that carries things back and forth from lunar orbit’. More recently, Free mentioned in the Selection Statement that the company plans to incorporate reusability ‘incrementally’.

Other factors also carry benefits for business. The easy ingress/egress process arising from the low entryway is not only great for astronauts, but cargo, too. The company also boasts plans to carry cargo into orbit from the surface (up to five metric tons) and, eventually, locally extracted oxygen (up to 21 metric tons) to replenish other spacecraft.

See also: How are we going to colonize the Moon?

Comparing Dynetics HLS with Other HLS Concepts

| Starship HLS | Blue Moon | Dynetics HLS | |

| Prime Contractor | SpaceX | Blue Origin | Dynetics |

| Design Approach | Single Stage Lander | Single Stage Lander | Single Stage Lander |

| Crew Capacity | 100 | Four | Two, maybe four (unclear) |

| Payload Capacity | 100 metric tons (reusable) | 20 metric tons (reusable), 30 metric tons (expended) | 12 metric tons (reusable), 30 metric tons (expended) |

| Propellant, propulsion system | Methalox, Raptor engine | Hydrolox, BE-7 engine | Methalox, unnamed engine |

| Planned Launch Vehicle | SpaceX Starship Superheavy | Blue Origin New Glenn | ULA Vulcan or NASA SLS (as of 2020) |

| Development Status | Flight testing ongoing | Not public | Hardware testing and demonstrations |

| Crewed Lunar Landing Contract with NASA | Artemis III

Artemis IV |

Artemis V | None |

See also: Blue Origin’s: Everything you need to know

Dynetics’ Collaboration in HLS Development

No HLS is an island, and that includes Dynetics’s vehicle. The lander is designed to work with NASA’s Artemis vehicles and infrastructure, including the SLS rocket, Orion spacecraft, and Gateway lunar station (which does not yet exist). As of 2020, the lander itself is to be launched aboard a Vulcan Centaur rocket or SLS Block 1B (an improved version of the rocket that flew in November 2022), though it is unclear how recent design updates have affected launch vehicle choice.

Once launched, the lander should be capable of docking to both the Orion crew module, which carries the astronauts, and the Gateway station. Dynetics also advertises its lander as compatible with not just NASA hardware, but commercial systems, too. That could help it work with commercial space stations or spacecraft to boost the lunar economy (this might involve transporting lunar material back to Earth, supplying craft with oxygen, or ferrying tourists to the lunar surface).

The development and manufacturing of the Dynetics HLS also involves much commercial collaboration. Though Dynetics serves as the prime contractor, the project relies on contributions from several other companies, including over 150 small businesses and some industry giants such as Northrop Grumman. Such a large group can be helpful in that it might provide access to more specialists and boost the companies and their local economies. On the other hand, spreading development so thin can make the process clunky and expensive.

Challenges in Dynetics HLS Development

Though Dynetics’s proposal is an interesting one, it is riddled with problems. These have been documented by NASA source selection papers, both in 2021 and 2023. Despite the updates made to the design between these dates, there are still several issues that stand out.

Before getting to the technical difficulties, it is obvious that Dynetics needs to work on its communication. In the 2023 selection statement, even Free had trouble understanding the lander(s)’s capabilities and whether they would meet mission specifications. This confusion arose twice in the report.

Firstly, it was not clear whether Dynetics HLS submitted design would allow for four crew members to visit the lunar surface. The report mentions that the company simply did not account for certain factors – such as the lunar spacesuits – and that updating the design to incorporate these would require a redesign of the crew module, causing cost overruns and delays. Then there is the debacle concerning the differences between the two landers in Dynetics’s proposal, wherein both vehicles were ‘mentioned in reference to the Crewed Demonstration Mission’, so the NASA report. Requirements for this mission – a roughly week-long stay on the moon – were not met equally by the two landers, with the CDM (Crewed Demonstration Mission) vehicle lagging behind. Free wrote that he was ‘highly concerned’ with these issues.

If ‘highly concerned’ sounds bad, try ‘deeply concerned’: Free’s feelings on the timeline provided by Dynetics for technology maturation. The report states that the design features eight critical yet relatively unproven technologies whose viabilities would be assessed during a single test flight – that would take place just nine months before the first crewed mission. If any of these technologies were to fail, little time would remain to update and further test the design before putting people in it and sending it to the moon. This would result in either a highly risky mission or countless delays, which mean even more cost overruns. These problems are not helped by the fact that Dynetics’s recent bid was reportedly a hefty chunk higher than the US $3.4 billion Blue Origin received. As a result, Free argued that the vehicle – whatever it is – is too risky and costly.

You may also like:

- How much does it cost to launch a rocket?

- Top 8 New Space Documentaries [+3 all-time classics]

- Top 6 SpaceX’s Goals and Objectives

Conclusion

In light of the above, it makes sense why other designs beat Dynetics HLS to the contracts. Technical issues, risky timelines, and confusing planning and communications cost the company its place in history. However, there might still be hope. In the selection statement, Free praised Dynetics’s mission flexibility and opportunities for business, as well as access to ‘six non-polar sites’ present in the solicitation. Also, NASA and Congress’s mission to create more competition in the field means giving companies like Dynetics second (or third) chances. Dynetics, for its part, does not intend to give up. After losing to Blue Origin in May 2023, the company emphasized that ‘the Artemis missions require multiple partners to achieve success, and our Leidos-Dynetics team is committed to continuing to assist on these critical missions,’ (as reported by SpaceNews).

Landing on the moon is and remains a seriously hairy process, and involves a vicious circle: doing so safely and successfully requires endless new technologies, but waiting until each of them is ready might mean waiting forever. At some point, it is time to jump: to decide on a design and stick with it. For SpaceX and Blue Origin, that time has come. Dynetics have not reached that point yet; perhaps it never will. Still, the recent rejection has granted the company a chance to update their design for potential future contracts. When the time comes, will it make the leap – or fall flat again?

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews and podcasts here.

Featured image: The Dynetics HLS team has completed several successful tests for their latest model. Credit: Leidos

Share this article: