by Julia Seibert

For the second time in human history, countries are ramping up efforts to gain the upper hand in matters of space as the sector swells with geopolitical significance. The modern space race, however, is a completely different beast than its retro counterpart. For one, technological gains have led to space transforming the way earthlings communicate and live, also playing a vital role by monitoring the planet to keep an eye on human or natural peculiarities. Coupled with new political landscapes and rivalries, advancements in the field bring forward the possibility of further space exploration and colonization, with some of the best space companies now leading the charge. Most strikingly, while such efforts are often (but not always) bound to governmental ambitions, they are increasingly carried out by the newest players in town: commercial companies.

Table of Contents

ToggleTypes of Space Companies and What They Do

This commercialization might be particularly obvious these days, but parts of it have been around since before humans landed on the moon (the Telstar 1 satellite, launched in 1962, constituted the first commercial use of space). Today, companies have saturated every aspect of the industry, and when we talk about the best space companies, we often refer to those that excel in each of these five main categories: launching, satellite manufacturing, satellite ground operations, orbital services, and technology relating to research and space exploration/colonization.

A large chunk of the manufacturing of satellites and some rockets is taken over by heavyweight contractors such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Airbus – but these are not solely space companies, often focusing on general aerospace and defense technologies. Also, some governmental agencies might function as a contractor themselves and can feature a commercial arm. The list below will focus on non-state companies whose primary specialism is space.

15+ Best Space Companies

Space Exploration Companies

ispace

The sobering moment when it became clear that ispace’s lunar lander’s touchdown on the moon had not gone smoothly was captured on livestream for all to see on April 25th, 2023. The lander’s failure (which also carried several customer payloads) was particularly painful as ispace was about to make history by becoming the first company to land on the moon – but the company has bigger plans, anyway. Based in Japan, ispace’s single focus is the moon: how to land on it, explore it, and, finally, live on it. On its website, a quick video goes over the company’s vision, which is to establish a populous city on the moon – called Moon Valley – within the century. The company’s next missions are more ambitious, involving rovers hunting for lunar resources to lay the groundwork for colonization.

Still, the title of first company on the moon might now be snapped up by US company Astrobotic, who had planned to launch its lander in 2023 (and deserves an honorable mention on this list). This company also recently won a NASA contract for its method of lunar power transmission. Still, the first lander is waiting for the readiness of ULA’s new Vulcan rocket. Another US company, Intuitive Machines, is also hoping to launch its first lunar lander in 2023.

Blue Origin

Blue Origin is better known for sending tourists to the edge of space and publicly squabbling with both SpaceX and Virgin Galactic, but its quiet strength lies in bolstering exploration efforts. With its lunar lander proposal already having been contracted by NASA (alongside SpaceX’s modified rocket design), the company was recently awarded another healthy sum by the agency to develop and demonstrate its Blue Alchemist technology: solar panels made from lunar regolith. This breakthrough, which Blue first unveiled in February 2023, could make significant strides toward colonization by providing future lunar cities with heaps of energy. Its method of in-situ resource utilization – using only locally available materials for a given process – could also be used for other purposes, including oxygen extraction and construction (as reported by Ars Technica). Blue Origin, known for its cutting-edge innovations, is also recognized as one of the best companies to work for, fostering a culture of excellence and exploration in the aerospace industry.

Visit company’s profile page.

See also: Blue Origin’S HLS

SpaceX

Today, SpaceX rules the launch industry, but tomorrow, its plans have more to do with space exploration and colonization. The company was born from a desire to reach Mars (and to build a vehicle capable of this), and the dawn of its colossal Starship rocket might symbolize the beginnings of this venture. Founder and CEO Elon Musk has mentioned a fleet of a thousand of these rockets (each of which can carry around 100 people, or about 100 tons, to the red planet while remaining reusable) leaving for Mars at once to establish a self-sustaining city there. Other than the prototypical Starship, no other rocket capable of such a feat exists. In addition to the company’s own plans, NASA awarded SpaceX two contracts for a modified Starship to land humans on the moon. In general, if the rocket’s advertised reusable payload capacity of 150 tons to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and cheap prices become a reality, it will pave the way for more entities – commercial or governmental – to launch bigger payloads, which could be a boon for exploration.

Visit company’s profile page.

Space Tech Companies

Astroscale

Astroscale is all about the orbit. It hopes to provide life extension as well as end-of-life solutions for satellites already circling the Earth while also cleaning up space debris. Headquartered in Tokyo but with subsidiaries scattered around the globe, the company has several projects in the works. Its ELSA-d mission, which launched in 2021 to test the end-of-life service, successfully demonstrated the necessary technology. ELSA-M, planned for 2025, will build on this technology with the hopes of eventually yanking defunct satellites out of orbit lest they become space junk. The launch of ADRAS-J, another one of the company’s spacecraft that hopes to take a closer peek at orbiting debris, is planned for 2023. Additionally, Astroscale’s US subsidiary is hoping to launch its LEXI mission by 2026. This spacecraft will fly to Geostationary Orbit (GEO) – the home of many old and expensive communications or spy satellites – and grab hold of them to extend their life.

Visit company’s profile page.

AstroForge

US company AstroForge has one goal, and one goal only: mining asteroids. The company is well aware of the dangers and difficulties of their chosen task, having witnessed previous space mining startups falter after offering investors overly optimistic timelines. Space mining, after all, is territory uncharted by earthlings. Therefore, AstroForge is taking its time to ensure its methods work. Its first two missions are set to launch within the next year; the first, carrying imitation asteroid material, aims to test out the extraction technology, while the second will fly by a certain asteroid to learn more about its composition. Though it may be a while before large-scale space mining comes to fruition, it would be vital for life beyond Earth, not to mention the astronomical profits coming to those involved. Plus, according to AstroForge CEO Matt Gialich, off-world mining helps decrease reliance on its Earthly counterpart, which is not exactly good for the climate (as reported by Meridian).

Visit company’s profile page.

Orbit Fab

Zooming around in space collecting debris and mining asteroids is all good and well, but what if you run out of juice? This is a problem that Orbit Fab, a US startup, looks to address. Advertising their services as ‘gas stations in space’, the company already completed a successful water transfer test aboard the ISS – the first of its kind – and launched the ‘first orbital fuel depot’ in 2021 (though this was still a test vehicle rather than a commercially available station). To ensure customers will be able to use its services, Orbit Fab developed RAFTI, an open-license fueling port that the company hopes will become the industry standard. By 2025, Orbit Fab aims to introduce the first orbital fuel delivery service for hydrazine, a chemical many satellites run on. While fuel prices on Earth are already steep, they are nothing compared to orbital rates: the company will charge ‘$20 million for up to 100-kilogram delivery’ of hydrazine. Orbit Fab also has contracts and agreements with a host of actors, including Astroscale and the US Space Force.

Visit company’s profile page.

Space Research Companies

SpacePharma

‘Bring your research idea and we make it happen’.

The slogan adorns the website of Israeli startup SpacePharma, which provides platforms for researchers hoping to try out their experiments in space. The company offers several different ‘labs’: smallish boxes containing mechanisms honed for cosmic experimentation. These can be used for a wide variety of disciplines, which the company lists on its site. Biology, for example, benefits from stem cell, aging, cancer, and microbial testing in space, as well as pharmaceutical research and production and fluid physics. While not all of its labs are designed for the ISS, many have flown aboard the station since 2017. The company has contributed to experiments including studying effects of microgravity on motor neuron cells, crystallization of an Asthma drug, and even how cow cells form muscles, or ‘steaks’, in microgravity for cellular agriculture company Aleph Farms.

Visit company’s profile page.

Space Forge

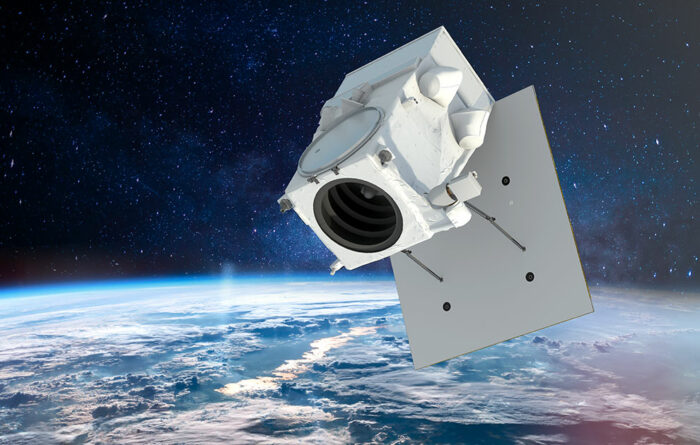

Research in space is already invaluable, but Space Forge hopes to take things one step further by providing a platform for entire product lines to be manufactured in space. The Welsh company bases its concept around the fact that elements such as microgravity and a vacuum greatly improve the quality of pharmaceuticals, certain alloys, and semiconductors. The latter, so the company, would experience a tenfold increase in quality if produced in space. Space Forge’s mini-factory – the ForgeStar satellite – is designed to be customizable according to client needs, and its time in orbit ranges from ten days to six months. Upon completion, the satellite reenters the atmosphere, its contents are collected, and it is then reused for another mission. Space Forge is not the only ones eyeing manufacturing, however; SpacePharma and Axiom, for example, offer preliminary production mechanisms, too.

Visit company’s profile page.

Origin Space

One could describe Origin Space as a simple space mining company, but its work is much more varied. In 2021, the Nanjing-based company launched NEO-1, a small satellite tasked with ‘small celestial body observation and prototype technology verification for space resource acquisition’. If that were not enough, the satellite would also test space debris cleanup methods. In addition to the busy NEO-1, the company has several other satellites in orbit, including two telescopes. The latest addition is YangWang 1 (‘Look Up 1’), which the company claims is the world’s first commercial ultraviolet/optical telescope. It recently completed an optical survey of the night sky, also keeping an eye out for pesky asteroids and meteors. The company ultimately hopes to build a constellation of telescopes to look out for juicy asteroids ripe for mining. Next, Origin Space is planning to send its M2 rover to the moon, which would carry imaging, mining, and sample return equipment.

Visit company’s profile page.

Space Satellite Companies

SES

Commercial communications and telecommunications satellites have been around for decades, and remain one of the prime commercial exploitations of orbit. A giant among giants of this industry is SES, headquartered in Luxembourg; this company has 70-odd satellites in two different orbits and claims to broadcast to around a billion people worldwide. It also provides network services to 58 government organizations. SES markets this connectivity to a variety of industries, including energy (providing connections to remote mining sites or offshore oil rigs), cruise ships, aviation, and military ventures.

Visit company’s profile page.

Maxar

If you watch the news, use Google Maps, or listen to the radio, you might have used Maxar’s products, as the company claims on its site. With over 80 satellites in orbit, Maxar provides some television and radio services but really shines at Earth imaging. The company is a darling of the US government, providing 90% of commercial imagery for geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), and recently upgraded its image definition from 30cm to 15 (for context, while the details of US spy satellites remain nebulous, they are thought to have a definition of around 10cm). Such high definition is important as it allows for more insight into risky areas without the need for drones; while the latter comes with the benefit of continuous observation, Maxar’s less eagle-eyed satellites can send back imagery of a given area 15 times a day. Maxar’s other services include the monitoring of factories and mining sites as well as methane emissions.

Visit company’s profile page.

Starlink

Starlink, SpaceX’s satellite internet service, has taken LEO by storm. As of July 2023, going on 4,900 of its satellites have been launched (with 4,487 still functioning): over half the current amount of working satellites, with thousands more in the works. The reason behind the mind-boggling numbers is simple: in order to achieve fast internet speeds, the satellites must be closer to Earth. As a result, a single satellite can only cover a small fraction of the Earth’s surface and stay over this area for a short amount of time. Starlink’s aim is therefore to build up a web of them to cover every angle of the globe. All those launch and manufacturing costs add up, and the company is just beginning to make money. Still, it has proven itself a valuable partner in defensive matters, providing drone support in the Ukraine war and frequently working with the US Air Force. Not everyone is happy with the concept, though. Astronomers, for one, are not amused by how the satellites can interfere with optical and radio astronomy. Plus, while the machines are maneuverable and are designed to deorbit themselves at the end of their lives, such a huge buildup of objects in orbit might exacerbate the growing problem of space debris.

Visit company’s profile page.

Best Rocket Launch Companies

SpaceX

SpaceX may harbor grand Martian dreams, but for now, the company’s daily bread is sending up one of its Falcon 9 (or sometimes Heavy) rockets at least once a week, on average. Payloads range from commercial payloads (including Starlink) to US national security satellites to science missions to humans. SpaceX is able to offer these launches at staggeringly low prices thanks to their reuse of the booster and fairing halves, which account for roughly 70% of manufacturing costs. The company charges around $67 million a launch, with the true cost much lower. The feat upended the industry, with other companies now fighting to catch up and integrate some aspect of reusability into their designs. With the potential for reusable rockets obvious, SpaceX is now developing the Starship, which it hopes will sink prices even more (if it is successful).

Visit company’s profile page.

See also: Top 6 SpaceX’s Goals

ULA

One of the companies threatened by SpaceX was United Launch Alliance (ULA), a joint venture between longtime government contractors Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Created in 2006, the company operates rockets previously under the control of the two companies, which included the Atlas V (Lockheed), Delta IV, and Delta IV Heavy (Boeing). As SpaceX’s impact was beginning to make itself felt, the company underwent restructuring in 2014 and vowed to slash launch costs. Now, with the veteran rockets facing retirement, that has not yet happened. Its new rocket, Vulcan, is slated to launch in late 2023 after facing delays to its upper stage and Blue Origin-made engines. Though the vehicle is not reusable, it can carry more than Falcon 9 with a projected launch cost of $110 million: not bad compared to the roughly $350 million for a Delta IV Heavy (which lifts about the same as Vulcan).

Space Pioneer

The need for reusable rockets was also felt in China, where the young company Space Pioneer – with its Tianlong-2 rocket – recently became the first of the country’s privately funded endeavors to successfully reach orbit with a liquid-fueled rocket; Space Pioneer also became the first company in history to achieve this on its first attempt. With the first launch out of the way, the company can now focus on reusability, which it hopes to implement with its Tianlong-3 rocket. The vehicle has a striking similarity to the Falcon 9, with the first stage ‘returning autonomously’ before being reused.

Visit company’s profile page.

Best Space Companies by Countries and Regions

European Companies

Europe is home to some of the biggest communications and telecommunications companies around, including SES, Eutelsat, Inmarsat, and Intelsat (though this is partially based in the US). It has also produced Airbus and Thales Alenia Space, who have contracted for a wide variety of space projects including the ISS and a slew of satellite systems. When it comes to launching, though, things are a little less peachy. Arianespace, a company created by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the French agency CNES in 1980, has ruled that particular landscape since its conception. Until SpaceX came around, it controlled up to 50% of the global launch market, and its Ariane rocket series had been a reliable workhorse of the industry.

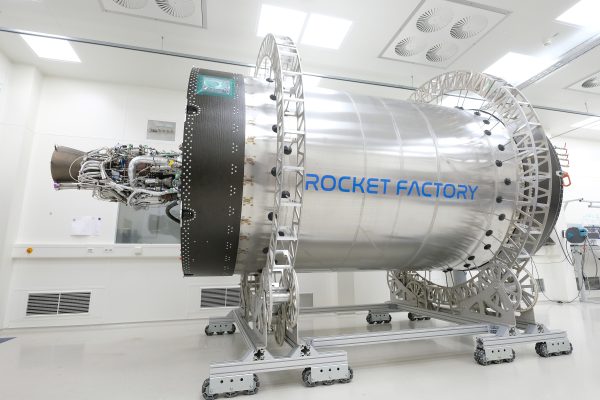

However, CNES’s shares in the company were bought up by now-majority shareholders ArianeGroup (previously Airbus Safran Launchers) in the mid-2010s, who made bold changes to the company’s newest vehicle in order to offer competitive costs. The rocket has faced significant delays and has still not flown, resulting in a launch gap in the European landscape. Still, a few young companies such as Skyrora, Orbex, Rocket Factory Augsburg, and Isar Aerospace, specialize in small rockets tailored to launching satellites and are looking to fill this gap.

See also: Top 6 Space Companies in Europe

US Space Companies

The US commercial space landscape… where to begin? The country has the most developed commercial space industry in the world, featuring both longtime government contractors like ULA (a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing) as well as newer players like SpaceX. The latter now controls a sizeable chunk of the modern launch market; in 2022, SpaceX alone accounted for about 33% of global launches and 70% of US launches. The country also hosts several up-and-coming launch companies such as Rocket Lab (founded in New Zealand but now registered in the US) and Firefly. Satellites are another vast area of focus impossible to wholly summarize here. A few examples are communications systems like those of Viasat, Echostar, and Starlink, and intelligence providers like Maxar, Planet, and Blacksky.

With such an industry (and infrastructure) in place, US governmental entities can pursue technological and geopolitical dominance in the space domain (at cheaper prices) while still fueling the economy and opening the door to even newer ventures. Some of these might include space tourism by the likes of Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, and Axiom; the latter two, as well as newcomer Vast, boast plans for space stations that would host tourists, professional astronauts, and researchers alike. Many companies developing technology primed for space exploration that has little use on Earth – such as Astrobotic, AstroForge, and (partially) Blue Origin – are also based in the US thanks to the industry’s importance and advancements.

See also:

- Astronaut Salary: How Much Do They Get Paid in 2024?

- Virgin Galactic vs Blue Origin – A Detailed Comparison in 2024

- ULA vs SpaceX – A Detailed Comparison in 2024

- SpaceX vs Blue Origin – A Detailed Comparison in 2024

Chinese Space Companies

With just 23 launches behind, China came hot on the heels of the US’s space dominance in 2022. The country’s launches consisted almost entirely of the Long March rocket series, which is operated by the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). More recently, however, the first private launch companies have been claiming their stake in the Chinese launch market after the government opened the door to such ventures in 2014. Space Pioneer is one, as well as LandSpace, LinkSpace, OneSpace, Galactic Energy, and i-Space (not to be confused with the Japanese ispace, which focuses on lunar missions). Clearly paying attention to industry trends, many of these companies’ designs feature elements vital to the most efficient rockets of the day, such as the Falcon 9. Most of the companies mentioned are aiming for some kind of reusability (some even hope to land boosters), while LandSpace recently beat SpaceX with the first-ever orbital methalox rocket. Non-launching startups such as satellite manufacturers Spacety and Origin Space have also made significant strides in recent years.

Indian Space Companies

India is also a relative newcomer when it comes to commercial space companies, as most of its cosmic activities have been instigated by the government. While the rockets operated by India’s agency ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation), are relatively cheap and have often been used for commercial purposes, a reshuffling of the sector in 2020 allowed private players to join the race. With such a young industry, most of India’s space startups are still finding their feet – but that is not to say the field is stagnant. Rocket startup Skyroot successfully launched its first test vehicle – India’s first private spaceflight – in November 2022, aiming to eventually offer regular flights of its Vikram series of cheap, nonreusable micro launchers designed for rapid deployment. Competitor AgniKul’s vehicle is primed for customization, promising different configurations of the rocket depending on the payload and access to a plethora of launch sites. Outside the launch scenes, several satellite startups are also making headway. Hyperspectral satellite imagery provider Pixxel, for example, is living the startup dream, receiving investment from Google and garnering a contract from the US’s NRO (National Reconnaissance Office).

You may also like:

Impact of Space Companies on Society and Industry

Privatization of areas previously handled almost exclusively by governments is nothing new, and its effects can be seen in the US’s various applications of the scheme. On one hand, it allows the government to spend less on its own programs, which (space-wise) are often politically sluggish and technologically low-risk as they cannot afford to fail. As seen with various military examples of outsourcing, the technique results in less government accountability, one way or another.

While this conundrum is prevalent in the space field, it also means that some of the best space companies can pursue riskier projects without facing the full brunt of political backlash. The service can then be bought by the government, which often pays far less than the cost of state-run development (a good example of this is SpaceX’s Falcon 9: a risky design that would have been near impossible for officials to sanction initially but is now the US government’s go-to). Conversely, as seen with programs such as NASA’s Artemis, outsourcing work to contractors creates jobs and economic growth even if the program itself moves relatively slowly. This highlights the fact that impressive industry numbers do not necessarily point to cosmic prowess. Still, other interests in space – geopolitical, scientific, and commercial – demand much innovation and enable new, even riskier ideas to join the party.

Future Space Industry Landscape

With the US’s surging commercialization of space transforming the landscape, other countries and regions are following suit. As a result, it is unlikely for the pattern to stop anytime soon. It is also hard to see how SpaceX’s hold on the industry could lessen – especially if its moonshot rocket Starship delivers on its promises – although it might face some competition from the likes of Rocket Lab (other startups like those from India and Europe might eventually join the club, but these are still in their relative infancy). Russia, a waning space heavyweight, sports a few space companies but ultimately missed the boat on large-scale commercialization and has now been sanctioned and isolated by much of the Western world. This means that many former customers of its cheap, reliable Soyuz rockets flock elsewhere (mostly the US), further lessening its role in the industry. China and its meteoric rise in both spaceflight and its commercialization is also likely to continue, even though the US’s extensive bans and restrictions on collaborations somewhat hold back goals of becoming an international space tech provider in the West.

The competition between the US and China is part of the reason for the so-called modern space race, with one constantly set on one-upping the other in orbit and beyond. This is leading to increased militarization of space, which – predominantly in the US – commercial companies are helping to bring about. The prospect is harrowing, especially considering previous implications of outsourcing in international conflicts. However, it is clear to see how these ambitions reflect on the industry, with a variety of launch and satellite providers tailoring their services towards government and military use.

In addition to orbit, though, both superpowers are gunning for their next prize: the moon. When (or if) this comes about, it could shape the future industry in the same way orbit’s geopolitical importance is molding the sector of today. Commercial sources of technologies such as mining, in-situ resource utilization, and deep space transportation are already being tapped by the US government, and a continuation of this pattern is likely if the space race evolves in this way. In turn, increased industry focus on (for example) lunar technology can incentivize other businesses to develop even more advanced technology and boost commercial opportunities.

Picturing what exactly this will look like is further complicated by international space laws, which are currently vague and outdated. They hold so little sway that the US created its own set of (albeit nonbinding) rules known as the Artemis Accords, which have now been signed by 28 countries. These make elegant use of the gaps in the aged UN treaties, laying the groundwork for space mining and claims of sovereignty that stretch existing laws. In addition, collecting signatories to the Accords in exchange for participation in NASA’s Artemis program helps the US establish a bloc-like alliance that nations will be reluctant to leave, helping it establish new norms for space exploration and countering rival powers. Once large-scale exploration, colonization, and mining kick-off, such blatant legal discrepancies could lead to further conflicts not just between nations, but between companies, too.

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews, and podcasts.

Featured image: Credit: ispace

Share this article: