by Julia Seibert

Why on Earth would anyone go to space? Outside the cushy confines of our home planet, the environment is deathly hostile, nightmarishly tricky to maneuver within, and above all, breathtakingly expensive to reach. And yet, its potential is vast. Governments and companies alike bank on satellites, which provide innumerable services vital to modern life. Celestial bodies contain riches just waiting to be mined. The orbital environment makes for a perfect place for a plethora of manufacturing processes to set up shop.

These opportunities, many of which have not yet been reaped, are now being eyed by a range of startups hoping to make their mark on the industry. While some focus on existing markets like satellites, others specialize in as-of-yet embryonic processes like mining and manufacturing and might help shape an entirely new industry. However, as the old saying goes, space is hard. The sector is defined by its high-risk, high-reward nature, which is why so much of it is dominated by governmental actors like NASA and industry titans like SpaceX. As the following space startups ramp up their efforts, only time will tell who will thrive, and who will succumb to the harsh reality of space.

Top 14 Space Startups

Orbex

Orbex was founded in 2015 under the name Moonspike, and its aim was to send a crowdfunded spacecraft to the moon. After failing to reach this goal, the startup was renamed Orbex in 2016 and focused its efforts towards launching small satellites into polar orbits from Sutherland Spaceport in Scotland. Thanks to developments in technology, small satellites are relatively cheap while remaining efficient for commercial and governmental purposes. Their launch is a priority in the UK sector, as detailed in its Space Strategy. Orbex’s rocket, Prime, is a two-stage partially reusable vehicle standing 19 meters tall. This space startup prides itself in its efforts towards environmental friendliness, including using low-carbon fuel along with launching from a carbon-neutral spaceport. The maiden flight is expected to happen this year, though an exact date is not yet known.

Visit company’s profile page.

Skyrora

Skyrora, like Orbex, is a space launch startup focusing on small satellite launches. The Edinburgh-headquartered space startup was founded in 2018 and already has a range of launches under its belt. These included liftoffs of Skylark Nano and Skylark Micro, both small suborbital rockets with one and two stages, respectively. In October 2022, Skyrora attempted its most ambitious launch yet with Skylark L, a single-stage suborbital rocket with 3D-printed engines and a guidance system, though the rocket experienced an anomaly shortly after takeoff and took a dive into the sea. Skyrora is now aiming to launch its next vehicle, the 22.7 meter-tall three-stage orbital rocket Skyrora XL, in the next year. The company’s other specialties include its mobile launch sites, allowing for set up and launch from a variety of places, a ‘space tug’ capable of taxiing payloads into specific orbits, and its Ecosine fuel, created from nonrecyclable plastic.

Visit company’s profile page.

Exo-Space

While some space startups hope to launch satellites, others’ missions start once these are in orbit. Exo-Space offers two main services, one of which is integrating clients’ “artificial intelligence/machine learning software models on Earth observation satellites without the customer having to launch their own.” Exo-Space provides a platform – FeatherEdge – with which the customer software is integrated. The imagery provided by the satellite can then be processed by this software, allowing for quick access to overhead data without the hassle of customers having to design their own hardware. The startup also offers its own analytics service: the Exo-Space Analytics Platform. Customers start by choosing what images they would like, and what insights are to be gleaned from them. Possible intelligence could include images of natural disasters like forest fires, or naval activity in a certain part of the world. The platform then runs artificial intelligence and machine learning models as the satellite imagery is collected, and this is then sent to the customer within the hour.

Visit company’s profile page.

Pixxel

Pixxel, a Bengaluru-based space imaging startup, was founded in 2018 by two final-year university students. Currently, the company has three satellites in orbit, with six more to follow in the next year. Its concept rides on hyperspectral imaging, wherein images are broken down into hundreds of wavelengths, revealing previously unseen details. The satellites themselves are tiny, weighing in at under 15 kg, but can spit out images only five meters in resolution. Today, Pixxel sets its sights on Earth. It hopes to use its satellites for better detection of agricultural trends, environmental health, urban developments, and mineral deposits. Even the secretive US National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) plans to use Pixxel’s imagery. In the future, this space startup is planning to look towards the solar system, forging plans to send a swarm of probes to search for off-world resources ripe for mining. With that, it can leverage in-space resources to shift heavy industry away from Earth, promoting a sustainable future.

Visit company’s profile page.

Helios

Israeli space startup, Helios, sees a market gap when it comes to lunar colonization: oxygen. The element’s liquid form is frequently used to power rockets as oxidizer, and together with fuel, it makes up the bulk of a rocket’s mass. This becomes a problem for establishing manned colonies beyond Earth. Processes such as shipping out massive loads of infrastructure and returning humans to Earth, are painfully difficult without refueling. Lunar regolith, however, is made up of around 45% oxygen, which Helios plans to draw out using its Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) reactor.

The machine would heat the lunar soil up until it melts, and then extract the good stuff. The process not only opens the door to tanking stations on the moon, but also allows Helios to ship the product elsewhere, making longer, more ambitious missions possible. While developing this mechanism, Helios discovered that this new extraction process also pops out 99% pure iron, using 50% less energy than the industry standard, eliminating all direct CO2 emissions.

Visit company’s profile page.

ClearSpace

Lausanne-based ClearSpace startup has a business model that is not centered around an opportunity of increased access to space, but rather a consequence of it. Space debris is a growing problem, with Earth’s orbit awash with thousands of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and millions of smaller bits and pieces. Junk too small to track is still extremely dangerous, with a single paint chip capable of ripping a bullet-wound like hole into a spacecraft. A single collision can create a surge of new debris, triggering a cascade known as Kessler syndrome that would make orbital activity extremely risky.

ClearSpace hopes to tackle this with its four-armed capture satellite, which will grasp onto a larger object and deorbit it to prevent a future collision. The company is already under contract with ESA to remove a 112-kg rocket stage in 2026 as part of its ClearSpace-1 mission. It has also been awarded a contract by the UK Space Agency (UKSA) to develop its design for the Clearing of the LEO Environment with Active Removal (CLEAR) mission.

Visit company’s profile page.

Astroscale

Astroscale also aims to make Earth’s orbit a better place. The space startup, based in Tokyo but with subsidiaries scattered around the world, sees multiple ways to make this happen; four, to be exact. The first is preventing debris from forming in the first place by deorbiting aging satellites, which the company refers to as End of Life (EOL) services. The next is Active Debris Removal (ADR): pretty self-explanatory. For functioning satellites that are running out of juice, the company proposes Life Extension (LEX).

This can take the form of on-orbit servicing or refueling, and a variation of the latter is currently in development by Astroscale US. Last is In Situ Space Situational Awareness (SSA), wherein a craft comes up close and personal with a potential piece of junk to assess its state and decide what to do about it. As of 2023, the decade-old company has launched two missions. The first, in 2017, was an SSA satellite that never reached orbit due to a launch failure. ELSA-d, a demonstration of its EOL services, launched successfully in 2021. Future projects include LEXI (a piggyback-style refueling method), ELSA-M (a more ambitious EOL mission), and ADRAS-J (a debris removal craft).

Visit company’s profile page.

Privateer

Privateer envisions yet another way to deal with space debris. Founded by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, this space startup collects data from ground radars to track satellites’ positions in orbit, and aims to provide data infrastructur’ and proprietary knowledge graph technology that can be used to avoid collisions. In March 2022, the company unveiled Wayfinder, an open-access and near real-time visualization of satellites and space debris orbiting our planet.

“We believe baseline universal collision analysis and risk assessment is the only path to space sustainability,” says Dr. Moriba Jah, Co-Founder and Chief Scientist at Privateer.

In October of that year, Privateer also released Crow’s Nest, a tool built using Wayfinder and NASA’s Conjunction Assessment Risk Analysis (CARA) to help with collision avoidance.

“Crow’s Nest keeps satellite operators, potentially preventing them from colliding with rockets and debris, to avoid a disruption of space activities, while Wayfinder… helps to ensure that humanity has access to space as a finite resource, in perpetuity,” explains Dr. Jah.

Visit company’s profile page.

Atomos Space

Remember those space tugs being developed by Skyrora? Atomos, founded in 2017 out of Denver, is a space startup, modeling its entire business around lugging satellites around in space, also advertising end-of-life services and servicing capabilities. The company’s linchpin seems to be its claim that the tugs will halve satellite launch costs, since satellites launched in rideshare missions by big rockets like the SpaceX Falcon 9 often maneuver themselves further to get to their desired orbits.

Instead of a satellite packing the extra fuel needed for these antics, Atomos’s tugs would instead haul it to its destination, before moving on to the next target. The first mission, planned for January 2024, will demonstrate rendezvous and docking capabilities, as well as the company’s electric propulsion powered by ammonia. Soon, however, Atomos hopes to make the switch to nuclear fission, which would allow the tugs to stay in space for longer.

Visit company’s profile page.

Space Forge

As Space Forge points out on their website, the space environment lends itself well to several manufacturing processes. Weightlessness, vacuum, sterility, and extreme variance in temperature can be godsends to the production of pharmaceuticals, alloys, fiber optic cables, and semiconductors. But while many companies, especially pharma giants like Merck, often fly experiments to the ISS to observe these effects, there is no way for the goods to be produced in orbit en masse. Welsh space startup Space Forge, founded in 2018, hopes to change this.

They would provide the platforms on which such manufacturing can take place, facilitating the process for outside companies. This platform, the ForgeStar satellite, is planned to operate like a mini factory in space. It launches with materials onboard, stays in orbit for up to six months, then comes back down and delivers the products. Whether the process works remains to be seen, since ForgeStar-0, an experimental mission and the company’s first launch, flew aboard Virgin Orbit’s doomed Start Me Up mission and tumbled back down to Earth. The next two models – ForgeStar-1 and 2 – are set to launch in 2023 and 2024/25, respectively. Space Forge hopes that the value of goods produced aboard ForgeStar 2 will surpass launch costs.

Visit company’s profile page.

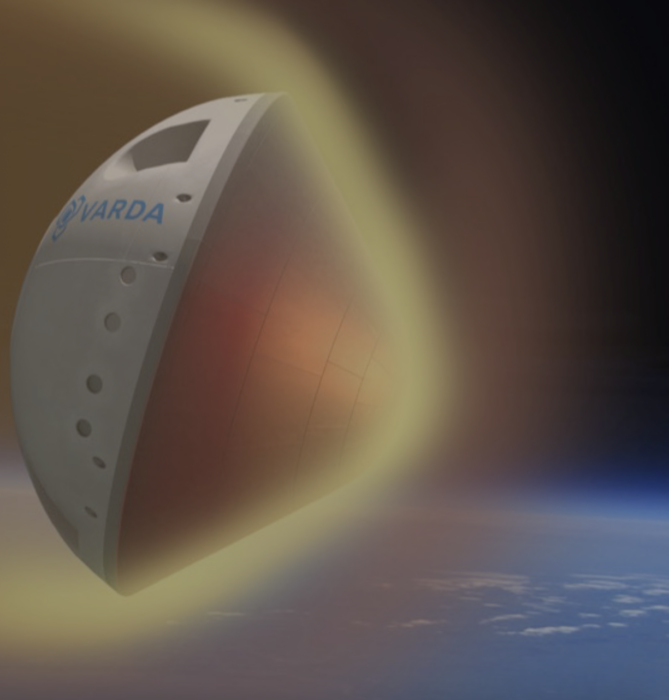

Varda Space Industries

The appeal of in-space manufacturing has also inspired Californian space startup Varda, founded in 2020. Its mission is building “the first space factory… essentially the first industrial park on orbit,” according to CEO Will Bruey, a former SpaceX employee. Its first vehicle is a manufacturing satellite, which it hopes to launch in 2023. The spacecraft consists of three parts: a Rocket Lab Photon spacecraft providing communications and flight control, the 120-kilogram Varda mini-factory, and a Varda reentry capsule.

The first mission should return only a few kilograms of product, with the aim of eventually bringing this up to 100 kg. The idea seems to hold water, since Varda bagged a NASA partnership for its 2023 flight, while the Air Force is interested in using the reentry capsules for hypersonic testing. Varda, however, has bigger ambitions. The company’s present Delian Asparouhov says that “as we start to scale, it allows us to send a larger space factory… eventually, yes, we might have something the size of the ISS, 10 times the size of the ISS.”

Visit company’s profile page.

AstroForge

In-space manufacturing already sounds wild, but space mining takes the cake in terms of incredulity. AstroForge, based in California and founded as a space startup in 2021, is willing to take on the challenge. Space, after all, is littered with asteroids containing rare Earth metals and Platinum Group Metals (PGMs), which are in high demand on the planet. AstroForge, who is set to launch its first two missions this year, takes an all-or-nothing approach to the concept, since the process is expensive and revenue, if any, will take decades to materialize.

Co-founder Matt Mialich, states that the company is prepared for this, and does not expect to earn a penny until an asteroid is mined. That, however, could take a while. The first mission, a technology demonstration, will carry imitation-asteroid dust, to be superheated and ionized in order to extract metals. Later this year, a bigger spacecraft will travel to a certain asteroid to check whether it is metallic. Combining the technologies to mine an asteroid is another matter completely, but these preliminary missions could indicate whether that is at all possible.

Visit company’s profile page.

Spaced Ventures

While some space startup companies mentioned above managed to snag hefty government grants, much of their capital comes from investors. Opening this process up to the average space nerd with a spare US $100 is what Spaced Ventures aims to do. It is essentially a crowdfunding platform for space startups, and has raised millions for a variety of companies since its beginnings in 2020.

Despite being marketed towards fledgling companies, it is industry giant SpaceX for whom the most has been raised through the platform. Though its recipient has not yet taken them up on it, over 2,000 people have invested almost US $40 million as of March 2023. But this is chump change for SpaceX these days, whereas the same amount could be life changing for a younger company. Provided a startup can generate the right amount of hype, investments made through Spaced Ventures could keep its vision afloat.

Visit company’s profile page.

Gilmour Space

Australia’s startup space agency only cut its ribbon in 2018, but Gilmour Space, founded 2012 in Singapore and now based in Queensland, Australia, has had its eye on the space industry for longer. The company focuses on smallsats, both their launch and manufacture. One of its G-class satellite buses is to launch on a rideshare mission in 2024, with capacity “roughly equivalent to the size, weight and volume of a large microwave oven.” Still, the bus, developed in collaboration with Queensland’s Griffith University, can carry “a lot of new space technologies that can be launched and tested in a single mission,” according to Shaun Kenyon, Gilmour’s Program Manager for Satellites.

In terms of rockets, Gilmour has attempted to launch two sounding rockets, the second of which never left the pad. Today, the 25-meter tall, three-stage Eris rocket is Gilmour’s pride and joy, and would be capable of launching 305 kg into low Earth orbit. Its first launches are scheduled for this year, with another to follow in late 2024. Gilmour has also partnered up with Atomos for collaboration on launches and customer missions.

Visit company’s profile page.

You may also like: 15 Most Exciting NewSpace Companies to Look Out for in 2023

Our Take on Innovations in the Space Startup Industry

While the space industry as a whole is on the rise, 2022 was brutal. The year saw an investment drop of 58%, thanks to economic shifts and ‘a dose of reality’ making its way through the industry, according to Tyler Letarte, AE Industrial Partners’ Vice President. Space, of course, is a high-risk business. Things blow up. Companies go under, not to even mention space startups… And as the industry blossoms, such patterns are making themselves clear to previously starry-eyed investors, who are now becoming increasingly selective.

On the other hand, the economic potentials of space are enormous, especially those relevant to governmental goals. Space Capital managing partner Chad Anderson notes that companies specializing in aspects applicable to defense and national security are most likely to survive. There is always a market for this, and government contracts already largely shape the industry, so that is unlikely to change.

Geopolitical competition, such as beating another country to the moon and its minerals, could add a new dimension to this. As a result, hesitant commercial investments could lead to the curbing of ventures not directly pertinent to government efforts. Still, says Anderson, tentative investors could help create a ‘more resilient’ sector, since weaker startups would be rooted out, so to speak.

Future of Space Startups

Since it is such a risky industry, future patterns of investment cannot be clearly predicted, but for those who are open to taking calculated risks, investing in the space industry could hold potential value. What is certain though, is that political interests will remain a forefront application of space technologies, and are likely to further shape the industry. What form this will take remains to be seen. If China were to colonize the moon tomorrow, for example, the US and its contractors would be right on its heels. This could then fuel private investment into the best space startups relevant to the effort, leaving less room for, say, debris removal.

Developments in technology, however, could have an effect too. Breakthroughs in previously unheard-of processes, such as in-space manufacturing and mining, could prove new concepts’ viabilities to investors. This depends largely on the performance of space startups such as Space Forge and AstroForge, who are on the brink of the earliest stages of testing. Space startups in the future must either sink or swim. If their technology fails too many times, their existence might be reduced to a flash in the pan of industrializing space. However, if they succeed, they could shape humanity’s future.

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews, and podcasts.

Featured image: Falcon 9. Credit: SpaceX

Share this article: