Astronomy is the study of celestial objects beyond Earth’s atmosphere, for which amateur and professional astronomers use telescopes. However, Earth-based telescopes are harder and harder to use for this purpose as it is more difficult than ever to see an unobstructed view of the sky. Why is this?

Polluted Night Sky

Light pollution and its elements like glare (excessive brightness causing visual discomfort), skyglow (brightening of the sky over inhabited areas), light trespass (light reaching places where it is not intended or even needed) and clutter (excessive groupings of light sources) all contribute to the struggles of astronomers. Furthermore, the light the moon casts on Earth, weather conditions like clouds, and satellites can also obstruct our view of the night sky.

Dark sky maps and lists of dark sky places do exist, however, not everyone has the opportunity to visit these. Professor Thomas Schildknecht, Director of the Swiss Optical Ground Station and Geodynamics Observatory Zimmerwald and Vice-Director of the Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern, Switzerland thinks that people have the right to an unpolluted night sky, no matter where they live:

“This is a human heritage. Humans have been looking up to the stars for thousands of years and then have been wondering what’s up there,” he said.

Another issue that astronomers have to deal with is the approximately 5-300 tonnes of cosmic dust that reaches our atmosphere on a daily basis. If this natural dust was not enough, there has been about a 5% increase in night sky brightness due to artificial dust originating from space debris. In addition, there are also thousands of currently operating satellites reflecting sunlight, of which 1700 were launched last year alone. Also last year, Rwanda announced its plans to launch a constellation of 327,320 satellites. In the next five years, another 20,000 satellites are expected to be added to the already congested low Earth orbit (LEO) and/or geostationary orbit (GEO).

Space Debris

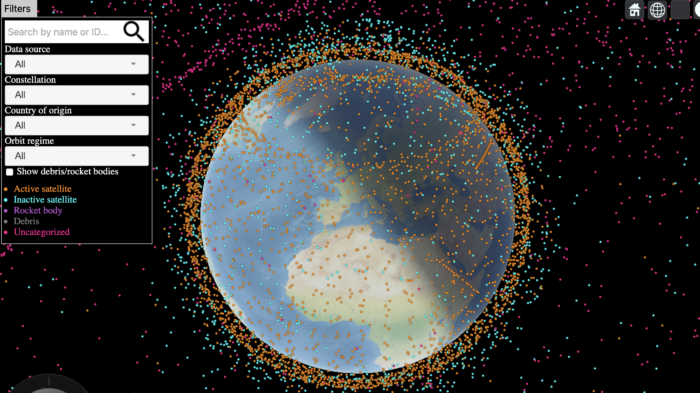

The European Space Agency (ESA) defines space debris as ”all non-functional, artificial objects, including fragments and elements thereof, in Earth orbit or re-entering into Earth’s atmosphere.” This can mean defunct satellites and other space junk with sizes ranging from a speck of paint to the size of a school bus. Nonetheless, about 95% of the objects tracked orbiting above our head is useless debris.

The problem with space debris of course, goes further than just obstructing our view of the night sky. These orbiting objects are travelling at 28,264 kph and they can collide and break up into smaller pieces causing a chain reaction, called Kessler Syndrome. All these pieces are of different sizes, they are at different orbits and they have different speeds. According to ESA, there are currently about 128 million pieces of debris smaller than 1 cm, 900,000 pieces of space junk under 10 cm, and 34,000 pieces over 10 cm in size in orbit around the Earth. Humanity currently does not have the technology to track anything below the size of 10 cm.

If orbiting debris hits key infrastructure, that can have devastating effects on our daily life on Earth and it can also put astronauts’ life in danger. A piece of space junk the size of a mobile phone could „cause serious damage to the ISS and kill people on board, or take out an entire network of communication satellites,” says Astrodynamicist Dr Moriba Jah, Co-Founder and Chief Scientist of Privateer Space.

There have been several examples of space debris hitting orbiting infrastructure in the past years, including causing a whole on the International Space Station’s (ISS) Canadarm2 robotic arm, as well as a chip in a window of the ISS. In addition, the space station has to be evacuated and has to conduct avoidance maneuvers regularly to move out of the way of space junk. Satellites often have to move out of the way of space debris as well. All in all, there are about 4500 close approaches to key infrastructure every year and satellites cannot always be moved.

On Earth, we have seen rocket bodies, such as the Chinese Long March rocket, re-entering the atmosphere in an uncontrolled manner. Larger, sturdier fragments of space debris made of high-melting steel or titanium alloys do not fully burn up in the atmosphere and crash into the surface. This is of course, is hazardous, as it can fall onto habited areas and can damage buildings or worse. In November 2021, Russia’s Direct Ascent Anti-satellite Test (DASAT) caused further fragmentation in space when the country destroyed one of its own satellites in orbit with the help of a weapon.

Space Sustainability

When we talk about sustainable space, it is important to explain what we mean by that. We need satellites for our banking, positioning, navigation, we use them for Earth observation to help mitigate climate change issues, agriculture, fishing etc. However, countries and entrepreneurs want to secure orbital slots and spectrum advantages, thus many of them are planning mega constellations which will make it harder to avoid collisions.

Being sustainable should mean not exhausting orbits around Earth. It should mean that although technical developments are necessary, there should be limits and agreements to preserve the orbital environment.

Viktoria Urban, Editorial Director of Space Impulse examined this issue during her talk “Calming the Sky Back” at the Astronomical Society of Edinburgh last week. To watch the recording, click here.

Featured image: M107 globular cluster. Credit: NASA

If you found this article to be informative, you can explore more current space news, exclusives, interviews and podcasts here.

Share this article: